This week,

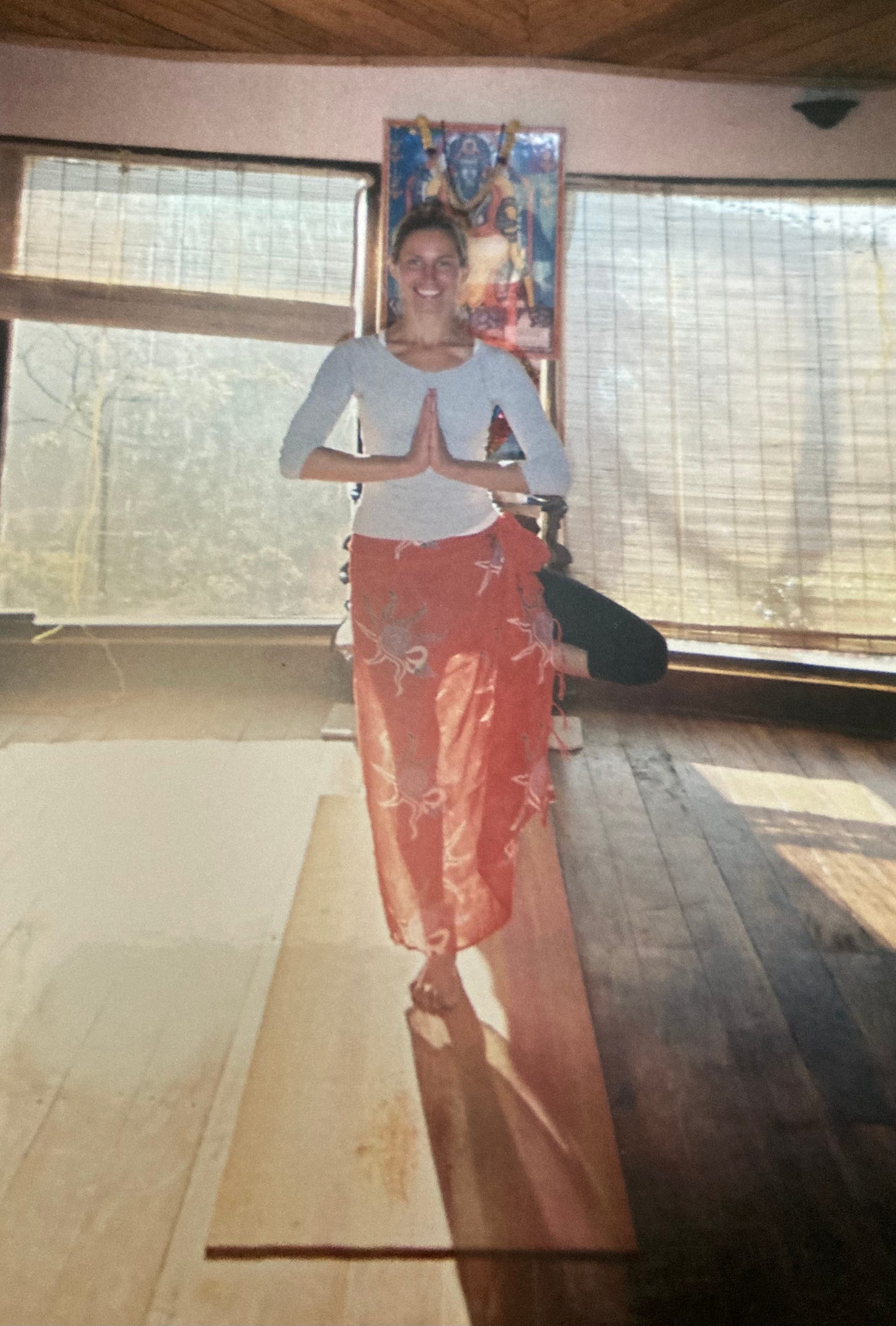

tackled the controversial topic of ‘cultural vulturism’ in his post The Ambani Wedding and Cultural Vultures in Publishing, in which he admitted to be “intrigued by the insight into Indian culture” and thought it would be cool to write a novel in that setting. But after the initial creative excitement, he immediately asked if it would be okay for him to write a novel set in India, if he had never set foot in the country. Are his curiosity and his friendships with Indian friends “enough of a prerequisite”?My gut reaction was, oh, oh. A risky endeavour. But probably less riskier for someone like Kern to attempt it, than for someone like me to attempt it, in the skin that I am - even if I did spend two and a half (transformative) months in India, not only travelling, but completing a rigorous yoga teacher’s training. It was in Coonoor, India, that I met my future husband and followed him to Canada. The rest is history, and a story that I am writing right now.

But I wouldn’t dare to write a story about India and Indian people for two reasons: 1) I am not confident enough in my ability as a writer to do the culture justice. 2) I expect to be crucified if I did.

It was bad enough when I wrote a story with a female character who was German (and not Hungarian) from the perspective of a man. My friend who worked for the Canada Council for the Arts warned me that I might be accused of “cultural appropriation.” Not for the German part, but for the male part, because I was a female. I was also advised to make the gay character in the story straight (because I was straight), even if he was based on my friend who happens to be gay. Needless to say, my wish to turn this short story into a full-length novel never got funding from the CCA.

I understand where the sensitivity to cultural appropriation comes from. How many white writers can you name, who referred to indigenous people in their work as “primitive,” and/or “savages,” pretending to know anything about indigenous culture, only to exploit it for a good story? How many times have marginalized groups been ignored, silenced and misrepresented? The crucial contribution of writers like Toni Morrison, Maya Angelou, James Baldwin, Witi Ihimaera and Ali Cobby Eckermann, Arapera Hineira Blank and Terese Marie Mailhot (to name just a few of the writers I read) is that they give voice to the complex reality of these groups, from their lived experience. Also, they have happened to produce some of the most stunning pieces of literature. As a reader, I must admit that I naturally gravitate towards their stories of overcoming and becoming, because I am always wanting to learn more. I’m grateful that these voices exist. I choose to read their writing for the same reason that I chose to complete a yoga teacher’s training in India and not in an air-conditioned yoga studio in London.

But as it often happens with progress, well-meaning, positive attitudes can be taken to some ridiculous extremes. If as a Hungarian-born writer, I am limited to writing from the perspective of a European straight female at all times, I can’t help feeling that something in the foundation of literature - the power of imagination - is lost. If you are genuinely curious about another culture, and language, and go to great lengths to learn about it, research it, and your intention is to approach it with reverence and respect - are you still a vulture?

I recognized the same thought echoed in multi-lingual writer Elif Shafak’s inspiring Ted Talk The Politics of Fiction:

“When identity politics tries to put labels on us, it is our freedom of imagination that is in danger.”

Kern’s post made me dig a little deeper, and ask myself bigger questions about identity, and why I feel so irritated when I am cued to choose an identity box when I apply for a grant, or submit my writing to a literary magazine. These boxes tend to be limited to my race, gender and physical ability, and do not represent my complex reality.

I don’t identify as “a Hungarian writer,” but prefer to say “a writer born in Hungary.” To be “a Hungarian writer” suggests to me that I am some sort of an ambassador to Hungarian culture, and that is too much responsibility on one writer’s shoulder. When I mention that I grew up in Israel, people automatically assume that I am Jewish. Yet I am not. But I was top of my class in Hebrew, Bible Studies and literature and love to celebrate Shabbat (have I confused you enough?). I have been living in Montreal since 2007, but prefer to say that I am “currently living in Montreal,” because I am never sure for how long this will continue to be my reality.

These three cultures/settings have obviously influenced my writing a great deal, and I am not at all ashamed to admit this, but they don’t define it, or me.

Searching for that illusive ‘home’ and a sense of belonging dominated much of my writing in my twenties, and perhaps is best expressed in my play “Someplace Else,” which, ironically, was presented by the Hungarian Culture Centre in London. I used to mourn the fact that I didn’t belong to one culture, which I could call “home” until I came to the liberating realization (in the bathroom, from all places) in my mid-thirties that my only solid home through all these moves had been my writing. While my identity kept evolving, and I continued to add one more language to my repertoire, my writing remained constant.

As I grew older, I have learned to appreciate my outsider stance and see it as an asset: to have an intimate knowledge of a country and language, but perhaps less of the bias that come with belonging to a specific identity group. I love Hungary and Israel, even when I condemn their intolerant politics. My political views are progressive, but I won’t be calling anyone “deplorable.” I may have some questions for a Trump, Orban or Netanyahu supporter, but I will listen to what they have to say and seek to understand first, even if I’m likely to find their views upsetting.

This is how I continue to grow as a human being, and growth is rarely comfortable. Growth is also impossible in the absence of an open mind. And for me, that is the true definition of the word ‘progressive’: “developing gradually, or in stages.” It suggests a constant state of flux and evolution.

Perhaps that is why when I’m forced to pick an identity box, I am tempted to write “an endlessly curious human being,” which says more about who I am than the words ‘white, straight, female, Hungarian, Israeli, Canadian.’ Probably also because the association we have with these words is that of ‘privilege.’ My personal and financial struggles are not tattooed into my skin, and on first appearances you might assume (as did my best friend Claire in London) that I have rich parents who support me, and not just a special talent in stretching a forty-pound weekly au-pair budget to a maximum, and a great eye for sales :) I don’t recall a question in my grant application that asked me about my financial circumstances, and no literary magazine stated in their submission page that “struggling single mothers are encouraged to apply.” And even if they did, would I want my temporary state as a single-mother define me as a writer?

I write predominantly in English, my third-speaking language, although the other five languages that I speak somehow always find their way into my writing. A writer friend once suggested that I could define myself as “linguistically queer,” which would be a pretty accurate description of my writing style - if we define queerness as “strange; odd, out of the ordinary,” and not limited to what ‘queerness’ is most known for, “denoting or relating to a sexual or gender identity that does not correspond to established ideas of sexuality and gender, especially heterosexual norms.” But again, I concluded that such descriptions would be risky to assume.

We could argue that these are first-world problems to have, and I am inclined to agree with you. Only a safe, tolerant and democratic society can afford to ask such privileged questions about identity. I acknowledge this, and I am grateful to be raising my daughters in such a society. But in this privileged and progressive society, I can’t help but wish that we weren’t always so quick to jump into labelling everything and everyone.

I remember how upset my twelve year old daughter was when her classmates labelled her as “A sexual” because she didn’t have a particularly strong opinion on her gender and sex. It was only months before that she had learned the meaning of the word ‘masturbation’ and she was grossed out by the idea. When her hair was short and she was not mistaken for a boy, she was often asked if she liked girls. She was not interested in answering any of these questions. Yet. I reassured her that it was perfectly okay.

“Why don’t you just be, sweetheart!?” I said. “And don’t worry so much about finding the right word to define that being? You have a lifetime to figure out who you are, where you are going, and what you want to be. And I’ll love you no matter who you choose to become.” I said all that, but I didn’t really have to. She already knew.

Ultimately, I think my aversion to labels comes from my belief that we have more in common than not. As James Baldwin beautifully said,

“But don’t you see? There’s nothing in me that is not in everybody else, and nothing in everybody else that is not in me.”

I believe that we are a complex composition of many things, and I wouldn’t want to limit myself to one thing. In that, I am with Tilda Swinton.

I don’t of course suggest that you abandon the identity that you are comfortable with if it brings you a sense of belonging and comfort. Who am I to judge? My great aunt found great comfort in Catholicism, and my mother in Judaism. I recognize the advantages that come with seeing yourself as part of a group and I will always respect the identity of your choosing. But like Tilda, I would prefer to see my own identity continue to evolve until the day I die, and I would prefer not to burden myself with a definition. And I would want my daughters to explore their own identities with the same kind of freedom, and not be cued into boxing themselves into more recognized, trendy choices.

As a society, I wish for us to break free from the clusters based on similarity, and keep a genuine curiosity towards the ‘other.’ And I wish for fiction to remain imaginative, respectful and expansive. Again, in the words of Elif Shafak:

Stories cannot demolish frontiers, but they can punch holes in our mental walls. And through those holes, we can get a glimpse of the other, and sometimes even like what we see.

Needless to say, you are welcome to challenge my beliefs, respectfully, or share your own story!

I dedicate much of my time, space and thought to these post, and you can always support me as a writer by sharing my posts and/or subscribe for free, or for the price of coffee a month! :) Every generous gesture is received with much gratitude. Thank you for reading me!

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/article/2024/jul/28/james-baldwin-taught-us-that-identities-can-help-us-to-locate-ourselves-but-they-trap-us-too

Relevant article in the Guardian this morning.

Identity is like my postal code. It helps get the mail to me, it just isn't who I am. I am not an object, some thought floating across consciousness. When I look inward to see who or what is experiencing all this, there is an encounter with awareness. Breathing in, I am aware of the feeling of being, without attributes. Staying in not knowing, I see through the silent, eyes of eternity. My heart breaks open.