A Mother’s Day special: a poem by Philip Larkin that you might be familiar with:

This Be The Verse

They fuck you up, your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra, just for you.

But they were fucked up in their turn

By fools in old-style hats and coats,

Who half the time were soppy-stern

And half at one another’s throats.

Man hands on misery to man.

It deepens like a coastal shelf.

Get out as early as you can,

And don’t have any kids yourself.Philip Larkin makes a valid point, and I agree with him, except on the last line.

There are countless ways we parents can fuck up our children. Besides the obvious, major life stressors like divorce, violence, abuse and neglect, we could sleep-train them and disrupt their healthy attachment patterns (Dr. Gábor Maté), we could coddle them and get them cell phones (social psychologist Johnathan Haidt), or send them to a bad therapist, who would end up doing more harm than good to their mental health (Abigail Shrier).

Listening to all these experts talk (usually while I cook dinner) I must admit that I feel uneasy. And guilty. I sleep-trained my eighteen-month-old daughter when I could no longer cope with the exhaustion of getting up in the middle of the night to nurse her. I held-off getting my daughters cell phones, but gave in to the pressure when they were the last kids in their classroom without a phone. I wouldn’t call myself a coddling parent, but I recognize my tendency to overcompensate my children for the lack that I felt as a child growing up in the 80’s and 90’s when it was perfectly normal to leave young children alone at night, or even alone in the country when you took a trip abroad (as long as you left them with envelopes of money). I am from a generation that is known to have raised itself (gen X). And if you are tempted to feel sorry for me, consider the circumstances in which my parents grew up. For a little context, consider this: poet Philip Larkin wrote the poem above in 1971. Therapy and self-improvement weren’t exactly a trend back then. Parents weren’t obsessing about their parenting skills, nor brooding over their traumas. Mothers smoked during their pregnancies, and maybe cut down on their alcohol consumption; and fathers, for the most part, were absent.

By stark contrast, parents today find plenty to feel guilty about.

Here is my story: I am a divorced, single mother and immigrant. My financial state would be classified as “a low income household.” So there you have it. My daughters are clearly doomed. I have set them up with plenty stressors and traumas for a life-time. You’d expect my daughters to suffer from serious mental health, lack of confidence and debilitating anxiety - characteristics now attributed to Gen Z - “the most anxious generation” of all, according to many experts.

Unfortunately, as much as I would love to dismiss these experts, I recognize that most of what they say is uncomfortably true. I see anxious young adults all around me. I became privy to this alarming trend while I was a mature student at university. What I saw between 2017-2021 as a parent of the previous generation raising the next generation gave me much to be concerned about: capable, smart and talented twenty-something-year-olds who missed classes, disrespected their teachers and expected to get top grades with the least amount of effort. Of course, not all students were like this. I met two of my closest friends at university - both incredibly resilient and hard-working young people who give me much hope about the future. But the sense of entitlement among other students was nauseating to watch. When a twenty-year-old adult told me how she was going to ask her mother call her ‘unreasonable teacher’ who had refused to let her off the hook for missing classes, my jaw practically dropped to the floor. I swiftly made the following mental note: I must do everything in my power to raise responsible and respectful young adults who will own-up to their mistakes and not feel like the world owes them anything.

I believe that my university experience (to use the current buzzword) ‘traumatized me.’ I am hyper sensitive to entitlement. Ask my fifteen-year-old daughter to tell you about the time I threw the sandwich I had prepared for her, at her, while yelling, “fuck you, make your own lunch then!” (Yes, I really did say those horrible words to her. Shame, shame, shame. And I’m sharing this with you here in case you think I’m a ‘zen mama’ and you feel bad about your own parenting skills). And what drove me to such despicable behaviour? The feeling that my then fourteen-year-old daughter, who was perfectly capable of making her own lunches (if she had bothered to get up early enough) was taking me for granted. Didn’t I have enough on my plate? Didn’t I pour enough love into everything that I did for her, including that sandwich, and didn’t I get up early enough to make sure she had everything she needed for school? I was indignant.

Luckily, it was precisely that low parenting moment that inspired one of the closest, and most honest moments between my teenage daughter and I. I apologized (profusely) for my bad language, and she apologized for her impatience. We both had a good cry and voiced our grievances, hugged, and moved on. Today she is responsible for her own lunches.

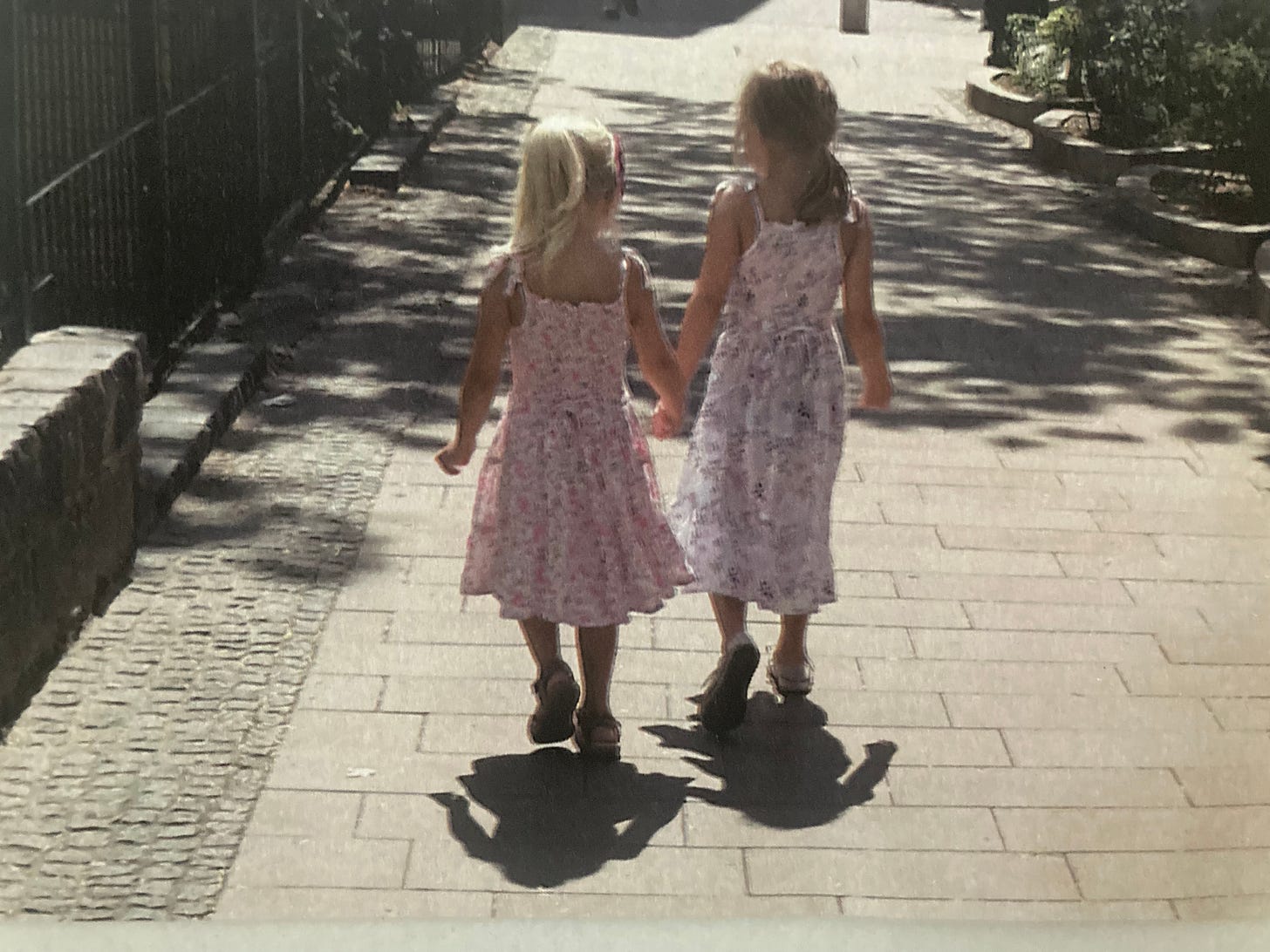

I wish it weren’t so, but I put my daughters through a lot. I had left their father twice with little else than a mattress and their work of art. The first time, I moved us into a run down apartment (aka the ‘shithole’) that my friend and I renovated with our bare hands. The second time, we were the lodgers at another family’s home, until (thanks to the help of a good friend) I was able to move us into ‘shithole #2’ that again I had to clean, renovate and refurbish. During this time I took on painting and renovating jobs (thanks to the new survival skills I had just learned) and cleaned houses for extra income. To graduate from university - which I somehow, miraculously, managed to do with ‘great distinction,’ I rose up early in the morning to cram in studies before making my girls breakfast. Looking back on those four years, I don’t know what made me pull through, but something deep within me refused to give up. And despite what my girls had witnessed in my marriage, I was adamant to give them a safe and secure base with the modest means that I had at my disposal. I avoided bad-mouthing their father, even at the toughest moments when all I wanted was to strangle him. He was their father and they had a different relationship with him. It would have been unfair (and unwise) of me to destroy that. I didn’t share my financial worries with my daughters, but worked hard at being financially responsible. None of it was easy. But in the space of five years my girls watched me leave a bad marriage, transform two shitholes into a ‘château,’ get a university degree, have my heart broken, and land two writing grants.

Do I wish I could have spared them the ordeal and raise them in a stable home, where their mother and father loved and respected each other? A thousand times yes! But life, unfortunately, didn’t work out this way. And here are some of the things that I noticed my daughters do as a result:

I watched my oldest daughter rise up early to study for her high-school entrance exam and be accepted to her preferred high-school. Both of my daughters take their studies seriously and do their homework without my help, and without me having to remind them about it.

They make their beds every morning and keep their room tidy.

They make their own breakfast, and often their own lunches and/or dinners. They can make their own matcha and coffee in the morning, but they ask me to make it for them, which I always do, happily, because it’s a gesture of love.

They thank me for every meal that I make, even those that they weren’t too crazy about.

They wash their own dishes, and we wash the dishes together after dinner (a great opportunity for me to catch up on what is trendy today in music).

It doesn’t take them long to apologize to me when they were rude, or mean.

They are not thrilled about vacuuming, but will do it when asked.

They babysit and tutor younger children.

They are there for their friends in times of need.

I am not sharing this with you to brag about my daughters, or my parenting skills (re-read my low parenting moment). My daughters are still normal teenagers who have perfected the art of eye-rolling. And if you need further proof, you are welcome to read my post on ‘the years of stupidity’ from last summer. I am also reluctant to take credit for their positive behaviour, as most of what they do is self-directed. But since I am a one-woman show, we had to have some difficult conversations and come to some agreements.

I recognize that my daughters’ main job right now is to study. Which is why I rarely ask them to vacuum and clean the bathroom. But what I do expect of them is to keep their quarters clean, empty and wash their thermoses without me having to remind them, prepare one meal a day, and be responsible for their school work. If they do all that, they save me most of the heavy-lifting work, prevent me from burning-out, and - allow us to have deeper, and more interesting conversations than argue about chores. I don’t want to be that nagging mother. It’s humiliating. For both of us. I am honest about these things with them because my daughters too have taught me some of the greatest, and most uncomfortable lessons.

When I was spinning out of control, they sat me down and told me that they would rather I asked for their help than me become the stressed-out-basket-case mother trying to do everything by herself. When I had my heart-broken, they reminded me that I should think more of myself, because no one makes a French onion soup as good as I do.

And my daughters have taught me much about resilience.

When I asked my September-born daughter who is the youngest in her class and is always working extra hard at her studies if we should get her tested for learning difficulties, she adamantly refused. “But we could make life easier for you. You could get concessions,” I said. “I don’t want any concessions,” she said. “Later in life I will have no concessions. It’s best that I learn to work hard now.” I remember stopping in my tracks to consider her point. She was right. Even if as a parent I wanted what was best, and easier for her.

This week it was my fifteen-year-old daughter that impressed me. She needs braces that are a costly expenditure that I cannot cover alone (the shame, shame, shame). She said that she would work this summer and pay for it herself. I insisted that braces are something that I feel parents should pay for. But what was I to do when I couldn’t afford to pay for it alone? My daughter and I came up with a plan of how to finance the braces together. At first, I felt a lot of shame. I don’t want my fifteen-year-old to have to pay for her braces. But seeing how empowered she felt by this decision, I was reminded of the sense of pride that comes from hard work. She will wear those braces with pride. And I have every faith in my daughter and I that we will find creative solutions to make the extra money - and that I can pay her portion back, because that is my secret plan.

Which brings me to the last point. As I began writing this post I mentioned that I was considered “low income household.” Something about writing those words didn’t feel right. I reject the label. Yes, my income is indeed low, but my daughters and I don’t live a “low income” life. We have little, but we have everything that we need. An affordable rental place with a toilet that takes two-three tries to flush properly, very little furniture and plenty space, few clothes (but a great sense of style) and many, many precious moments. (As I write this, my daughter just thanked me for “giving birth to the cutest little sister she could ask for”. And for me, this is priceless)

Yes, the experts are right. A divorce can be a serious disadvatage to children. So is growing up with a single parent. But much depends on our attitudes, and what we choose to model. And don’t parents give themselves enough of a hard time for the various ways they “fuck up” their children? Must we add up more to their guilt?

To Philip Larkin’s poem I would say, yes, it’s true: they fucked me up, my mum and dad. They didn’t mean to, but they did. Just as I did, and continue to do, fuck up my children. But hopefully not too much. Hopefully just enough so that they learn to be resilient. And hopefully, so that they grow up to be a better human being than me. And may my daughters learn from their future children what I keep learning from them about life, love and resilience. I have no regrets about having kids myself. It’s the best thing I have ever done. Despite my countless fuck-ups.

Happy Mother’s Day to all the hard-working, exhausted and guilt-driven mothers out there who do their best raising the next generation. Whatever you do, and however ‘well’ you do it - you have my deepest admiration and compassion.

And may we, parents, remember to give some of that love that we give so willingly and unconditionally to our children also to ourselves.

Love,

Imola

I love how you share that mothering these two young adults is a gift. You are doing great! I share a lot of the same values I embark on my kids for participation in the household. There’s no shame in making mistakes as parents as we learn from them. And there’s no shame in kids going to therapy to complain about us as they are. That’s how they individuate. Glad to be connected here, Imola!

Hi Imola. I finally had the time to give this piece the attention it truly deserves. I was deeply touched by many of the things you wrote. As millennial/Gen X parents, we often don’t give ourselves enough credit for the tremendous work we put into breaking transgenerational trauma. We are the first generation to tackle this challenge.

Does this work come easy? No. Do we make mistakes and sometimes repeat the patterns our parents set? Yes. But we also acknowledge those mistakes, apologise to our children, and strive to improve. This willingness to admit our faults and say "I’m sorry" sets us apart from previous generations.

We try harder to be better for our children, modelling resilience and demonstrating the courage to admit our mistakes and share the lessons we've learned.

We must remember that the companion to this work, shame, is a generational inheritance. Healing and liberating ourselves from it will take time. But with effort, we can hope not to pass it on to our children.