Last week I wrote about the gift of poetry. As promised, this post is about my process of writing poetry. But, what a surprise! As I looked through some of my old writing files in an attempt to find a poem for this post, I discovered an essay from 2019 that I wrote for Stephanie Bolster’s poetry class. Stephanie is an extraordinary, generous and kind teacher who had a huge impact on my writing. She is too humble to admit this, but it’s true. I wouldn’t be writing poetry today if it wasn’t for her unrelenting persistence. In one of our more recent conversations I admitted to her how insecure and intimidated I was at first in her poetry class, and to my great surprise, she admitted to me that she thought I was going to give her a hard time! In the end, I quickly relaxed in her class and far from giving her a hard time, I showed up every week like a faithful disciple, thirsty for knowledge and inspiration.

I was a little sad to read this essay because it was written two months before the dissolution of my marriage, and re-reading it now, it reminded me how impossibly hard it was to complete my degree with all that was going on in my life at the time. How I managed to graduate (during a pandemic!) with ‘great distinction’ is still a mystery to me. I must have been really determined. And, as difficult as it was to complete a degree with two young children, university provided me with structure and a much-needed focus.

But the following paragraph has also made me smile: “Who knows… my novel ‘You are a Mother Now’ might end up being a poetry collection? Or a combination of prose and poetry, fiction and non-fiction, in English with some French, Hungarian, Hebrew and Italian thrown in?” because as it happens, this is precisely what I am working on right now: turning that novel into an unconventionally structured story, with many poems!

Note how resistant I was to embrace the word ‘poet’. I crossed it out and replaced it with a more general ‘writer’. I stand by this choice. Not because I don’t believe that I could ever write anything as good as Elizabeth Bishop’s One Art (I don’t try), or because I think the word ‘poet’ is pretentious, but because I don’t like to limit myself to one thing. By being simply ‘a writer,’ I can write prose, plays and even poetry.

Attached to this post is also a fun poem inspired by my friend Vincent Pilkington-Landreville. Vincent and I had many soul-searching conversations after class and I remember joking with him about writing an alternative CV that listed our less conventional experiences and achievements - the ones that had taught us the most valuable life-lessons! The result is the poem Curriculum Vitae. I hope you’ll enjoy it.

(An essay for Stephanie Bolster’s Poetry class 5 February 2019)

Scribbles on Paper: A Poet’s Writer’s Statement

“Te mit értél el?” my father was yelling at me. We were at his local restaurant, but he didn’t seem to care, or hold back. In front of him there was a glass of beer, and a smaller glass of palinka. His girlfriend was silent, her head bowed down. It was the moment I decided to get up from the table. “What have you achieved?” he repeated, even louder, as if I were the deaf one, and not him. What have you achieved? would be my father’s last words to me, at the moment I decided to walk out on him, for good. I made sure to give his girlfriend a hug on my way out, as she was a decent and kind person. Perhaps too decent, and too kind. I then turned to my father and said, calmly, “What I have achieved, and have yet to achieve, is none of your business. I don’t care what you think of me.”

At the entrance of the restaurant, I was still angry. But as soon as I stepped onto the street, I felt strangely light, and – free. My mother was surprised to see me back at her apartment half an hour later. My father had specifically requested “a private meeting of three hours” while she baby-sat my ten and eight-year-old girls who were an inconvenient distraction from more important things, like him. Besides, they didn’t speak Hungarian.

“Ma kara?” What happened? she asked in Hebrew and was already reaching for a bottle of wine. My Israeli friend Ravit, whom I had met while serving in the IDF more than twenty years before, was also sitting at the table. But, ‘what happened?’ was not a real question, as they could already picture the scene perfectly in their heads. Ravit hugged me, while my mum poured us some wine. “Well, one thing is for sure,” my mother said, smiling. “Imola does not lack writing inspiration.”

“That is true,” I said. “But I have enough inspiration to last me a lifetime and not enough time to write about it. So, maybe you could stop acting crazy?”

Playwright David Hare said in an interview that his childhood in Sussex was so routine like and boring that he became a writer in order to give himself “a little excitement of life.” My world, by contrast, has always been much too ‘exciting.’ Family members would throw unthinkable insults at each other, engage in loud debates, violent outbursts and fits of jealousy. Reading Chekhov’s plays I always thought, this is my family, right here!

Writing was a way of keeping sane. The least I could do was to make good use of the drama and turn it into an entertaining piece of theatre. Drama seemed a natural path, although I came to playwriting via acting. I was never the girl who waited for things to happen to her. I preferred to make things happen for myself. Writing gave me the freedom to be creative without waiting around for the permission.

Reflecting back on my twenties, I marvel at the audacity with which I continued to write and travel as if nothing stood in my way. Not the fact that I was an immigrant with a funny accent writing in her third language, not the fact that I had no financial support from my parents, only my modest au-pair income, and not the fact that I was continually asked when I was going to “finally grow up.”

“Nothing else is worth my time” was my motto, which I delivered with a confident smile. There was always a way; if not the conventional way, then the Imola-way. If I wasn’t good enough for the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, I would write my own plays with a part for myself. I would travel to New Zealand with the first draft of my first screenplay and find me a producer. I would live in New York, learn Spanish in Madrid and do a yoga teacher’s training in India.

Then I got married and moved to Montréal. I was thirty-one and in love. How one writes about happiness? I was suddenly worried that in my happily-ever-after chapter I would find nothing to write about.

Motherhood

took over

my life.

The first time I sat alone in a café without a baby, I scribbled I AM SCARED in my notebook. “My soul is dying,” I sobbed, and begged my husband to free me up so I could write again. “Otherwise, you might as well lock me away with the loonies.” I warned him. “You are such an actress. Could you be more dramatic?” he replied. I didn’t know it then, but it was the moment our marriage began to die.

When writer (and mother of five) Louise Erdrich was asked how she finds the time to write, she replied: “I suspect it has to do with a small, incremental, persistent, insect like devotion to putting one word next to the next word.” Insect like devotion is the art I have learned to master. Rise up an hour or two before the rest of the house, lock myself in the bathroom, escape to the library, write next to my reading daughter, and even lie to carve writing time when there is none. Harder it is to brush off the accusations that writing is a “non-lucrative pursuit,” or worse, “a hobby,” and that I am selfish to dedicate time to it when more lucrative duties (like mothering) call my attention. I should think about my retirement instead and the girls’ activities. I am a mother now.

Time. I wish I had more of it.

I have no time to procrastinate. Life resists me enough. Either one of my daughters get sick, my computer dies unexpectedly, or, my husband picks a fight – and always before an exam or an important submission is due. It is as if life asked me, So, how much do you want this Imola? How hard are you prepared to fight for it?

Life would be easier without writing.

Perhaps.

But then –

I remember the feeling of emptiness I felt when I was kneeling in front of my husband, muttering my soul is dying. Or, the time I locked myself in the bathroom and scribbled on a piece of toilet paper writing is the only home I have ever had – a realization that surprised me in its simplicity. Searching for my place in the world had been the central theme of everything I wrote in my twenties, and the title of my play Someplace Else. Was this ‘home’ with me all along? How many plays did I have to write to arrive at this “one true sentence” (Ernest Hemingway)?

Writer Joan Didion said, “I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means. What I want and what I fear.”

Writing in order to understand is what drives me to the computer to “bleed” (Hemingway again). I don’t choose the subject; the subject chooses me. The more a topic scares me, the more I’m drawn to it. I embrace discomfort. I thrive on discomfort.

I had never dreamed of being a ‘playwright.’ Things may have turned out differently if the Royal Court Theatre hadn’t closed its Young Actors’ Programme. I may have never decided to give its Young Writers Programme a go. Or, had I not gone to see The Royal Shakespeare’s Company’s 1996 production of Midsummer Night’s Dream. Or had I not read Sophocles’ Antigone and Oedipus the King. But I suspect that writing would have found me sooner or later.

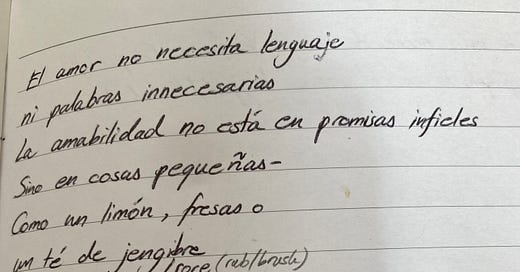

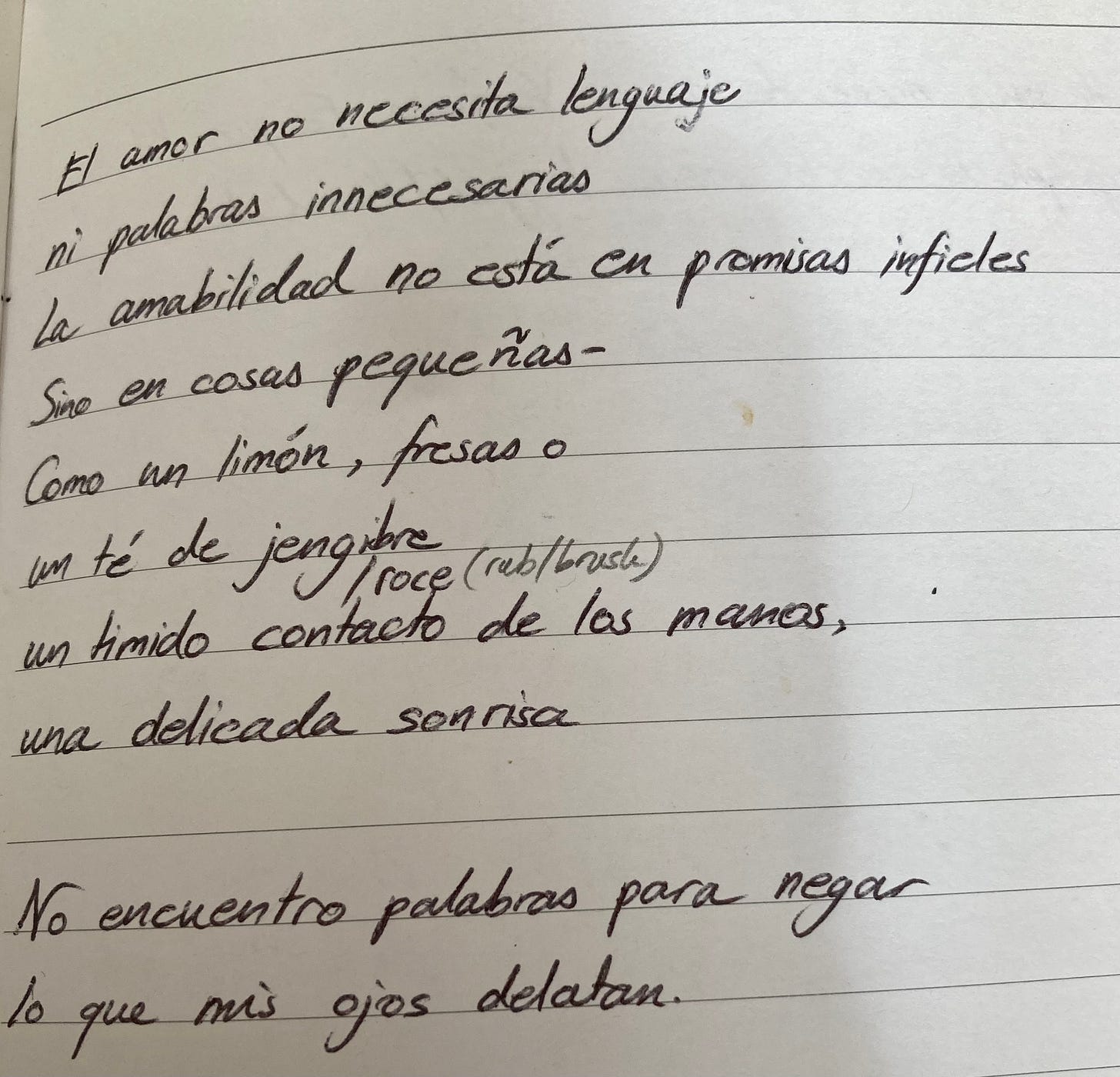

I never wanted to be a poet. Not because I didn’t like poetry, but because I didn’t think I was good enough to write it. Not in Hungarian, not in Hebrew and not in English. Writing dialogue is easier. All you have to do is eavesdrop discreetly with a pen and paper handy. Yet poetry, which I was careful enough to call “scribbles on paper,” was the first thing I attempted when I began learning Spanish, French and Italian. My limited vocabulary was my challenge: How could I express big thoughts with the simplest words? How could I play with language and turn it into something that sounded less like Spanish, French and Italian, but more “Imolanian”?

The economy of poetry suits my insect-like-devotion. I can try and capture a moment, a thought. There is an end in sight, which is harder to see with a novel of three-hundred pages. Who knows… my novel ‘You are a Mother Now’ might end up being a poetry collection? Or a combination of prose and poetry, fiction and non-fiction, in English with some French, Hungarian, Hebrew and Italian thrown in?

Still, I prefer the word writer. It feels more honest and less pretentious. It evades categorization and simply states an action: A writer is someone who writes. That is what I do. My dramatic background informs my poetry and prose, conversely, poetry leaks into my prose and plays. Whatever form my scribbles choose to take, they are my humble attempts at ascribing words to feelings, frustrations and love. They can be openly about ‘me’ as Curriculum Vitae, or less obviously like me as True Love: Quiz, or nothing like me as Katalin. But they came from me for a reason – conscious or unconscious.

Perhaps I am being selfish. After all, I am writing for myself. Even when writing feels more like a torture, it is when I feel most alive. When it flows, it is nothing less than magic. Exhilarating. The best natural drug in the world.

Writing is my drug.

I always rise up a changed person from my seat having written. And if I’m lucky enough to have stumbled on a true sentence, writing teaches me truths that I can no longer ignore. It forces me to take action like a warrior woman. Writing helps me make sense of a senseless world. With writing I can (try) to capture the beauty, hope and humour found in the bleakest of moments. First, I have to write through the darkness to arrive at the light, but it is always the light that I am searching for.

Writing is a gift. Writing is not only my home, but my best friend. So are the books that I read. I read on the bus, I read on the plane, I read while I wait; I read first thing in the morning and last thing before I go to bed. I read in English, Hungarian, Hebrew and French, and at the moment – with some difficulty – in Italian. I listen to The New Yorker podcasts and Writers and Company as I cook and fold laundry. It turns the most tedious domestic choir into a stimulating experience.

I suppose what I’m after is not just writing tips, but inspirations for the kind of life I want to lead. And while literature cannot save the world, it has saved me. Time and time again.

What have I achieved? I could have easily answered my father, but I didn’t want my words to fall on deaf ears. It wasn’t a real question, but I’m glad he asked it because the answer in my head was clear. My greatest achievement in life, as I see it, has little to do with writing and more to do with the friendships I have made, the experiences I have had, and the girls I am raising. It isn’t something I can put on a resume, but it is something without which life would amount to nothing. The legacy of my words matters, but the legacy of my actions matters even more. So, as my friend Amelie says, “je mets mes pantalon” and show up. I try, I fail, I get up, and try again. I write.

Curriculum Vitae

NAME:

• Imola – like the city in the province of Bologna in northern Italy

• Not Italian. No links to the Formula One racetrack

• A tip for correct pronunciation: imagine you are Italian

• Zs pronounced like J in je t’aime

• (a futile anecdote, just for fun: I was called אסתר for a quarter of my life)

DATE OF BIRTH:

• I embrace each year

CITIZENSHIP:

• Of Nowhere and Everywhere. My national anthem is John Lennon’s Imagine

(I dream of New Zealand)

ADDRESS:

• A shithole I have turned into a château with white paint and hard work

TELEPHONE:

• Is on silent anyway, so why bother

MARITAL STATUS:

• Separated. Liberated. In transition

• “If you are afraid of loneliness, don’t marry,” said Anton Chekhov

• “We are all crazy,” says Alain de Botton

• “Marriage is a crapshoot,” says my friend Erin

LANGUAGES:

• Mai napig csak

• שֵׁשׁ

• but

• esto es solo el comienzo

• il y a toujours plus à apprendre, n'est-ce pas?

• chi lo sa

• vielleicht lerne ich Deutsch als nächstes?

EDUCATION:

• Communism, my father’s alcoholism, my mother’s migraines, religion (a double whammy of Judeo-Catholic guilt), kibbutznikim (those manyaks), Greek tragedies, a broken heart, picking oranges, M-16 & Uzi (no, it is not sexy), the London theatre, Shakespeare, a broken heart (for real this time), Courage Workshop for Big Emotions, Royal Court Young Writers Programme, New York City, Madrid, Pedro Almodovar, Aotearoa, yoga, India, marriage, Montréal, Celeste, Eliane, Simone de Beauvoir, adenocarcinoma in situ, Concordia University, Italian, separation, reconciliation, separation, liberation, renovation, transition…

DREAMS/GOALS/ASPIRATIONS:

• I’ll whisper them to you in confidence

Hi Imola, I am new to poetry and have had many of the same feelings of inadequacy as I approach it. I too love the economy of words in a poem--what a way to pack a punch! You're writing is beautiful, and can't wait to read your poems. I just subscribed!

Thanks for this. Imolanian! So great! And add courage and authenticity to what you've achieved. xoxo