I wish I were one of those people who sprints out of bed early in the morning to exercise, but I am not. I like to wake up gently, make myself a nice cup of coffee and head back to bed – to read. I call this time ‘my sacred coffee time’ – a time of pleasure, a little gift to myself before my daughter Eliane shakes me, and asks me to make her morning matcha and braid her hair in a very particular way (long, thin braids with no loose hair). I try not to rush this moment, even if it means waking up twenty minutes earlier, when the house is still cold and it is dark outside. Far from a “guilty pleasure,” I have found that this simple ritual, first thing in the morning, can make all the difference between me starting the day on the right foot (centred, focused, kind), or the wrong one (irritated, resentful, scattered). The bleaker the weather is outside and the longer is my to-do list, the more determined I am to protect this time, in which I fill my well with beauty and inspiration.

What can I say? I have always been a nerd (secchiona). I love to study, I love to read, I love to bury my head in books and forget where I am. But nothing raises my energies and level of happiness (felicità) like reading in Italian. In the case of Italian, reading the phone book out loud would suffice, but I decided to aim a little higher.

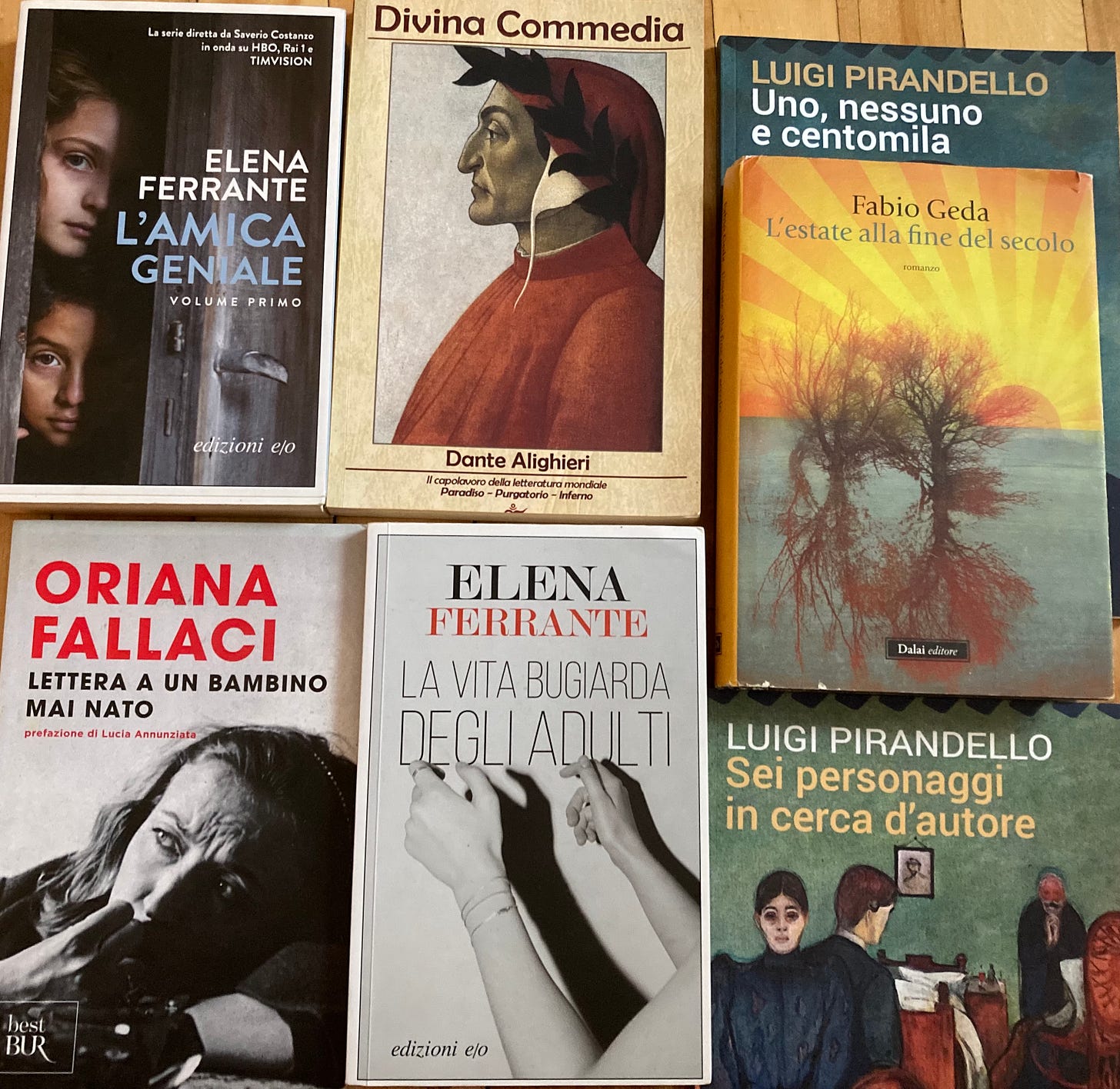

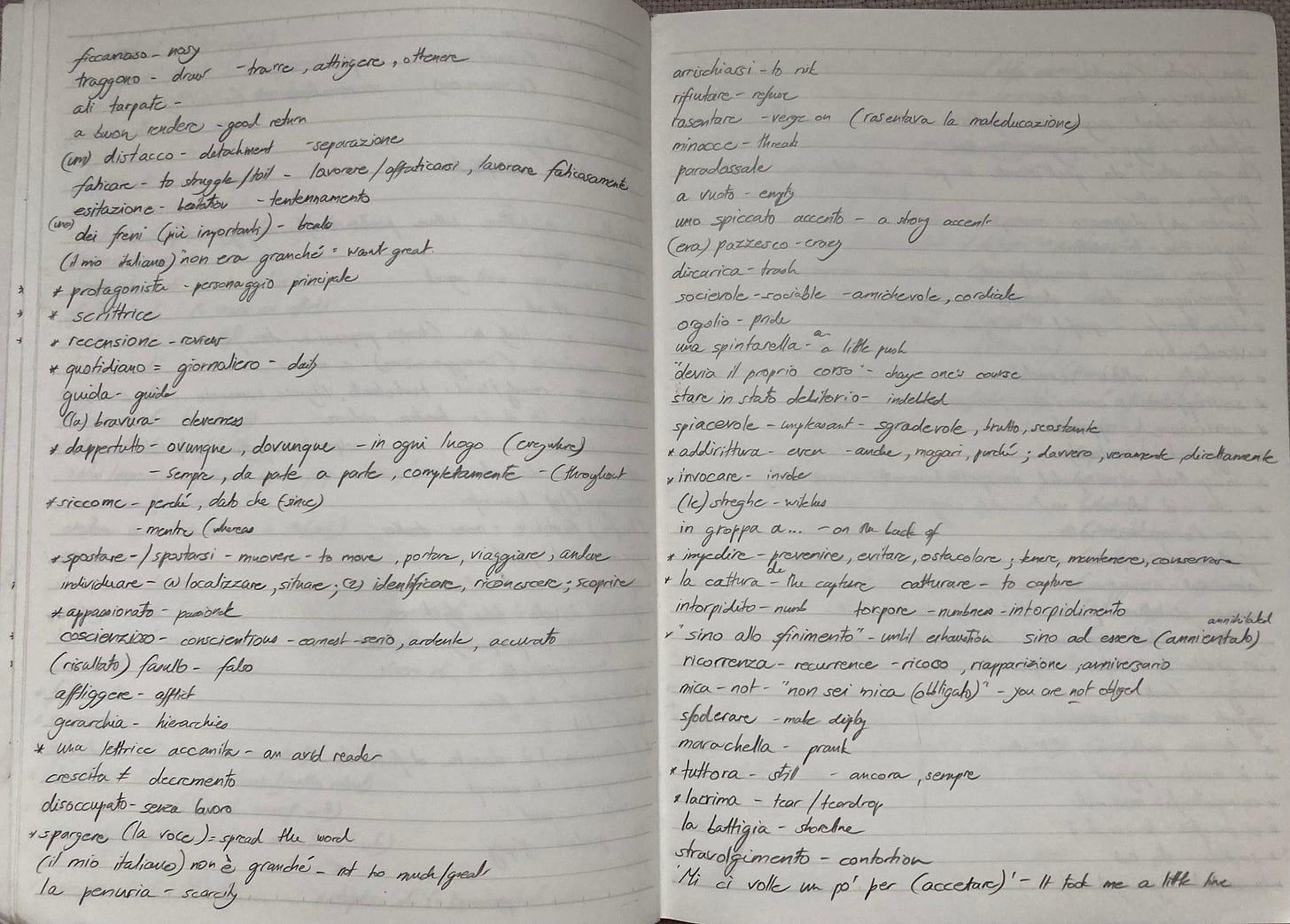

The first book I read in Italian was Elena Ferrante’s L’amica geniale, which I had already read in English. It started off as a deeply frustrating experience. I was slow and needed to look up many words in the dictionary, which I carefully captured in my Italian notebook. It felt like I did more writing than reading. It took me close to two weeks to get through the first forty pages of the book. I was tempted to give up, but couldn’t, because I needed to read the book for my Italian course at university. But at around forty pages, something miraculous happened. I began to speed up. Fast. And by the last fifty pages of the book, I hardly needed to look up any words in the dictionary.

This experience encouraged me to dive into Fabio Geda’s L’estate alla fine del secolo. Geda’s prose was more sophisticated than Ferrante’s, and I hadn’t read him in English. This made the reading more difficult, but also more rewarding. Each time I captured a new word in my notebook, I felt like I was given a precious gift. Imprescindibile (indispensable), coinvolgimento (involvement), impavidamente (fearlessly) – my Italian vocabulary was expanding!

Next, I took on Oriana Fallaci’s Lettera a un bambino mai nato, which I had read in both Hungarian (first) and English (second). Pure poetry, from the very first sentence: Stanotte ho saputo che c’eri: una goccia di vita scappata dal nulla (Last night I knew you existed: a drop of life escaped from nothingness). I devoured the book, I highlighted sentences, and wrote my first essay in Italian, “Sull’amore e la libertà: Una lettera ad Oriana Fallaci,” as a creative response to it. Reading Natalia Ginzburg’s short play Fragola e panna felt like a breather after this exercise, but it also inspired me to write my first short play in Italian, “Il fetore della maternità.”

During the pandemic, a friend was kind to lend me Italo Calvino’s Il barone rampante, which felt like a formidable challenge. The book was abundant in metaphors and subtle philosophy, and rich in botanical vocabulary. It was hard work that took me a couple of months to complete. But by the end of the challenge, I was ready to tackle Mount Everest of Italian literature: Dante Alighieri’s Divina Commedia.

Dante kept me company through most of the pandemic. One canto a day, I promised myself. I first read it in Italian out loud, focusing (hard) on trying to understand as much as I could from the text. Then I read the same canto in its English translation, after which I returned to reading the original Italian text. It was a labour of love. I became ossessionata with Dante and the history behind the Divine Comedy. My daughter Celeste rolled her eyes whenever she caught me in my reading corner, muttering incoherent words in a foreign language like a sorcière. “Again you with your incantations?” She’d make fun of me. But she wasn’t entirely wrong. Reading Dante out loud in Italian became my daily prayer, a magic spell that worked like a charm in uplifting my spirits in the darkest days of the pandemic. Quindi, Italian became my anti-depressant, my pillola della felicità, my happiness pill. In November 2021, when my former Italian teacher asked me if I would participate in a Dante Marathon organized by the University of Turin, I couldn’t think of a more intimidating challenge. I feared that my obscure mutterings of the Commedia were not up to scratch with what this sacred text demanded: a perfect pronunciation and prosody of Old Italian. But of course, I couldn’t say no. The greater (and crazier?) the Italian challenge, the more likely I am to take it on. Once standing upon what I thought was the peak of Mount Everest, I realized that I wasn’t even close. My mission is not limited to speaking fluent Italian, and reading Dante in Old Italian. I’ll reach Mount Everest (maybe?) when I can write a play, inspired by Dante – in Italian. And to reach that ambitious peak, there is a steep climb that will take a lot of hard work, patience and perseverance to complete.

In the meanwhile, I continue to read. And, I continue to write. Colpo di fulmine is my first attempt at writing a poem in Italian. It is not Dante, but I have to start somewhere.

It's marvellous that you learnt Italian through reading. I was reading your post awestruck with a smile on my face. And I enjoyed Colpo di fulmine very much. I lived in Italy for three years almost 20 years ago and since then never kept up with my Italian. It's at the stage of "conversational" now. But I'll try to write something, simpler perhaps, in Italian, see how that goes along.

What languages do you write in? And what type of writing do you do in different languages? I haven't yet gone through your posts (only read this one just now), so perhaps I might find an answer there.

I'm Romanian, but haven't lived there over 20 years. I lived in Argentina for over 8 years and now in the UK for 8 years. I took in English since a toddler from cartoons on the telly, though only now I've been living in an English speaking country. So I always wrote and write mostly in English. A fair amount is in Spanish as well, but I struggle so much to write in Romanian (though I do a bit) or Italian. I struggle in the sense that it simply doesn't come naturally. Then of course, I lack much practice in both.

I'm just sort of getting going on Substack (I don't have much to show). I feel quite daunted by it all. But I knew since I got the Substack going that I'll be publishing poems in three languages, except in Italian (for now).

Thanks for sharing your reading/learning experience. I'll grab a book in Italian and see what happens!