To be called a ‘dreamer’ is never a good thing. No one ever says to you, “good for you for being such a dreamer!” When people call you a dreamer, it is usually their polite way of telling you that your aspirations are out of touch with ‘reality’.

I have been called a dreamer, or less polite versions of the word dreamer all my life. I am still that dreamer, and here is why.

1. DREAMING AS ESCAPISM

My childhood wasn’t particularly fun, and dreaming gave me an escape route to an imagined world. I probably shouldn’t have watched those Fellini and Almodóvar films as young as I did, but the beauty of the Italian language and the Spanish rhythm of life allowed me to dream of a world where dreamers like me could one day belong.

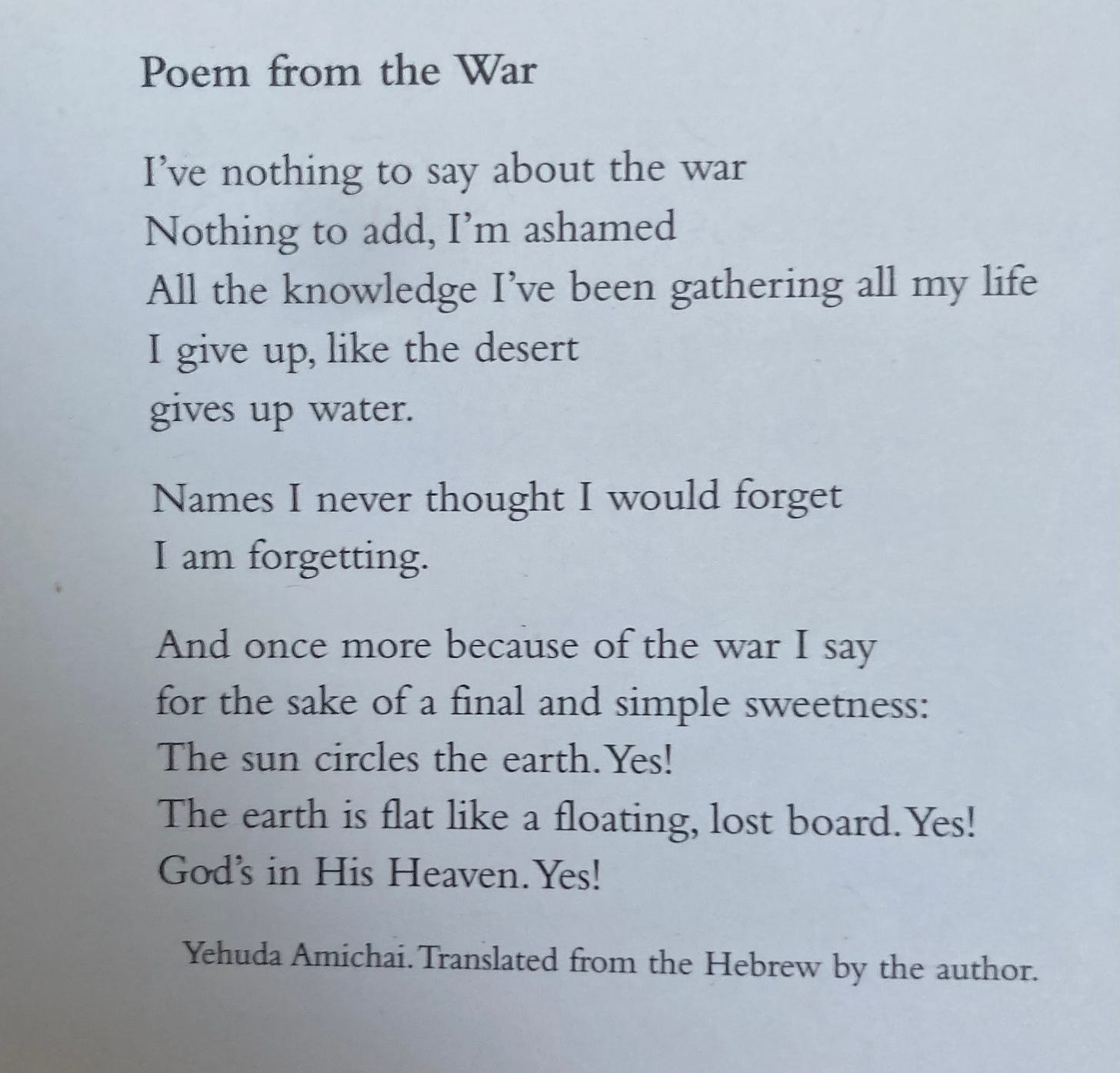

My life in the kibbutz by stark contrast was dreary. An education that had little to offer me in terms of variety, and even less to stimulate my curious mind. The Hebrew poets we studied (Bialik and Amichai) put me to sleep in the classroom. Some excitement was finally injected into our sterile literature classes with the arrival of Antigone. And I was the weird kid who read the rest of Sophocles’ plays in her spare time while others, as my brother pointed out to me later with pride, “were busy screwing in the groves.”

2. IMAGINING A BIGGER PICTURE

I was also reading the poetry of Hannah Szenes, the young Hungarian Jewish resistant fighter who was executed by my countrymen in 1944 during Hungary’s Nazi occupation. During those years I hated my country of origin and sent my father letters with the Hungarian flag crossed over and the Israeli flag in a big red heart.

One third of my history classes were dedicated to studying about the holocaust, another third to Zionism, and in the time that was left we skimmed through some other noteworthy events like the Spanish civil war and Pearl Harbour. Figures like Lenin, Stalin and Mao Zedong were briefly mentioned.

I was curious to learn about the past, even if the past was dark and often horrifying to explore. I wanted to know more. I wanted to understand what drove Hitler to such levels of hatred that resulted in the death of six million Jews. In my studies of the aspirational Zionist movement the land of Israel was described as largely empty. “A land without people for people without a land.” For my high-school avodat gemer (final work/thesis) I chose “The Neo-Nazism in Germany” as the cheerful subject to explore in depth. My uncomfortable conclusion? That the Germans were not a special breed of evil but that people of all ethnic background were capable of similar evils (as we briefly touched upon in those condensed world history classes). More disturbingly, I suspected that the potential to do good and the potential to inflict great harm existed also within me, as in all human beings.

This was before I learned about Hannah Arendt and her (in)famous Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (1963), The Milgram Shock Experiment (1963) and the controversial Stanford Prison Experiment (1971). These were absent from my history classes and I learned about them in my adult years, in psychology.

But a similar sentiment had been echoed by my Bible Studies teacher. My Bible Studies teacher was a religious man who lived outside the peripheries of our secular, leftist kibbutz. He read the Old Testament in a booming, passionate voice to a crowd of bored kids whose only interest was to pass the final exam with a 55 point mark. I was catching up on some sleep in his class until I heard him say, “We say that we are the chosen people, but we have stolen, murdered and did all the horrible things that others have done. We are no better.” I wish I could remember which passage he read out loud when he said that, but it was the moment I woke up in his class and began to pay attention. My Bible Studies teacher earned my respect because he was a devout Jewish man who was proud of his faith, but was also a critical thinker. During those “years of stupidity” (what we call adolescence in Hebrew), I didn’t yet know how important critical thinking would become for me. But I already had a sneaking suspicion that I was told only one side of the story, and that there was a larger, more complex story to be explored.

3. TESTING MY BELIEFS

I was seventeen years old when a nineteen year old soldier handed me an M-16 and ordered me to shoot it. It was our pre-tironut (“apprenticeship”) and nothing about this scene seemed abnormal to my fellow kibbutznikim. I was the only one who cried. I closed my eyes and aimed into the distance and shot until there were no bullets left in the gun.

I was nineteen when during the real tironut we were instructed to pledge allegiance to our country by bringing the bible (“a symbol of our heritage, culture and history”) to the gun (“the ability to protect it”). Luckily for me, the crowd was big enough so they couldn’t see me refuse these orders. “The bible and a gun” to me, were far from “a beautiful combination,” but reminiscent of something I recognized from the enemy that we were supposed to fight.

I was twenty-five and living in London when I first heard the word nakba. The Palestinian ‘catastrophe’ of 1948 that resulted in the violent displacement of Palestinians from their land, property and belonging hadn’t been mentioned in my history classes when we were celebrating the “Day of Independence” and the founding of the Jewish State in the historic land of the Jewish people: a land without people for people without a land.

The Royal Court Theatre was showing Ramallah’s Al-Kasaba Theatre’s Alive from Palestine. I remember how deeper and deeper I sank into my chair during the play. My eyes were searching desperately for fellow Israelis in the audience. This can’t be true, I thought. Israel is a democratic country. These things cannot be happening in a democratic country. It was the first time I heard about the Palestinian daily reality of searches at checkpoints, stifling poverty and casual bloodshed – only a few kilometres from where I used to enjoy my cappuccinos. My younger brother at the time was serving in the IDF.

The play was followed by a talk and drinks at the bar. I was approached by one of the actresses in the play (I guess I hadn’t managed to sink low enough in my chair and cry discreetly enough). She tapped on my shoulder and I fell into her arms, sobbing. “I’m so sorry.” I kept repeating the sentence like a prayer, or a forlorn mantra. “I’m so sorry for everything. I didn’t know this was happening.”

It was the first time I encountered a Palestinian person, and the first time I heard a very different version to the story I had been told. But what could I do to change the world? Who am I to bring on change? I couldn’t even convince the people closest to me to see Palestinian people as human beings, and not just human shields, or terrorists.

But at the Royal Court Theatre’s bar, sobbing on Georgina’s shoulder, I desperately wanted to believe in this dream: that my friends and family will see what I see; that the world will see what I see, and do something about it.

4. I HAVE A DREAM

“I have a dream,” said Martin Luther King Jr. in one of the most memorable, aspirational speeches on freedom and equality. Martin Luther King Jr. had a dream in 1963 that he dared to hold as a self-evident truth: “that all men are created equal.” He said, “I have a dream today,” and followed it by saying, “I have a dream that one day –” He was assassinated in 1968 before he could see his dream (imperfectly, but significantly) come true. As was another non-violent resistance leader, Mahātmā Gandhi, who inspired many civil rights movements across the world.

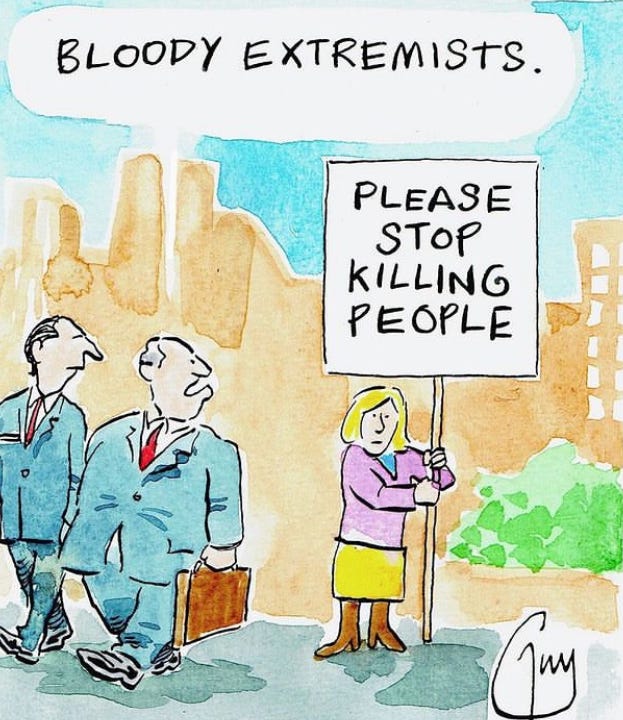

Which begs the question: what is it about peace that is so threatening? Why dreaming of peace is considered “radical”? And why waging a merciless war is considered “realistic” and the only feasible solution? To want to extinguish hate and violence with more hate and violence – how is it logical? And how is it working out so far?

Alive from Palestine was staged at the Royal Court Theatre in 2001. Twenty-three years later the images from Gaza look like a scene from a science fiction movie: a living space reduced to rubble and dust, children with blown up limbs, mothers mourning their dead children, men stripped to their underwear at gunpoint, paramedics shot to death in the ambulance a block away from the six year old girl they were trying to rescue – also shot to death with her family in the car, and the famine that is now ravaging Gaza, while trucks with the necessary aid are blocked by Israeli protesters wrapped in the Israeli flag, singing am Israel hai, and the United States is air-dropping food to desperate Gazans, while continuing to provide military aid to the war machine that is killing them, but I…

I am the crazy one. The one with the radical views. The yafat nefesh (“beautiful soul”) who “should do her proper research” and “educate herself.” I am assured that the IDF is “the most ethical army in the world,” despite the videos that I had seen some Israeli soldiers post on social media in Hebrew, which unfortunately I understand. I am told that this is the only way to get the Israeli hostages that are still in captivity, and are hopefully alive still (I am praying). I am told that all nameless thirty thousand dead, without exception, are “terrorists.” Including the dead babies. I am reminded that as an Israeli, I should know my place and be supportive.

I want to look away from the horror. I can’t take it anymore. There is this heaviness in my heart ever since October 7 that has only gotten heavier. The only place where I have managed to find a momentary relief is in the Mile End Chavurah’s Sabbath service. There, among other Jews and non-Jews who live this conflict in their hearts, it seems acceptable, and even normal, to sing Sabbath songs in Hebrew, talk openly about “stopping the war in our own hearts,” pray for the safe return of the Israeli hostages in captivity, as well as the safety of “our Palestinian brothers and sisters.” There, I can finally cry. And I always do. There, I am reminded of everything that I love and admire about the Jewish religion: the ongoing aspiration to do good, to do better. Because to be the chosen people is not just a privilege, but also a responsibility. There, where we can celebrate our shared humanity first, I dare to dream of peace.

5. THE SOLUTION?

One of the questions I am asked the most by my (realistic) critics is, “what is the solution then, if not this?” It is almost funny that I should be the one coming up with the solution to a problem that no one so far has managed to solve in seventy-five years, but here is my best shot:

Please watch this conversation with Ali Abu Awwad and Amir Dar. I don’t want to provide a quick summary, because I’m hoping that you would actually watch this 43 minute talk. And “Listen for a testament to the resilience of the human spirit and the belief that, despite entrenched conflict, a shared commitment to dignity and justice is possible.” Ali’s story shows how despite the unimaginable trauma that he had gone through, an unorthodox choice put him on a very different path.

Then, my suggestion is that we elect people like Ali and Amir as government officials instead of the hateful demagogues that we currently have in power, on both sides.

And then, alongside remembering what is admirable and worthy of pride in being Jewish or Palestinian, we may also want to remind ourselves of what it is to be a human being and stop the dehumanization of people outside of our group of people. An Israeli dead baby and a Palestinian dead baby is still a dead baby, and too horrible to contemplate.

Then, we may want to exercise some critical thinking and take a hard look at ourselves. Where does our moral compass lie? Are we closer to our capacity of doing good, or our capacity of inflicting harm? This is deeply uncomfortable at first, but the only way, I believe, towards true growth. This is not a “progressive” aspiration, but a human aspiration. And for the sake of our future generation, we must engage in this work. This is not “self-loathing,” but a self-respecting, revolutionary act of resistance.

When the heaviness in my heart makes it difficult for me to breathe, I remind myself of this simple truth: my part in this conflict may be small, and seem insignificant, but imagine if we all made this tiny adjustment: we saw people as people first. The world would be a different place.

Now, this is a dream worth dreaming.

This is an incredible piece of writing Imola. Your experiences are really interesting to read about, and I think your messages concerning Isreal and Palestine are important for people to hear. I hope this gets shared.

thanks for this Imola. i find it comforting to know that people like Ami and Ali are out there, sharing their vision for peace.